How Majority Rule Wouldn't Have Done Anything

| Categories: academic, statsEric Maskin and Amartya Sen write in the New York Times that US primary and general elections would be more fair if the winner always commanded an absolute majority of the popular vote. Perhaps, but as it currently stands, neither party nominations nor Presidential elections are actually decided by the popular vote. Even if Maskin and Sen’s criteria were satisfied — and a Presidential candidate’s state victories were all absolute majorities — that candidate could still technically win a Presidential election with only 23% of the popular vote.

State-by-state majorities don’t mean a national majority

Maskin and Sen’s claim is that the voting system used in primaries and Presidential elections produces winners who only got more votes than each of the other candidates (a plurality), rather than a majority of the votes. For example, a candidate can win such a contest with 40% of the vote if two opponents get 30% each. They suggest this voting system should be replaced with one which fulfils the Condorcet criterion: if there is a candidate who would beat each of the others in one-on-one contests, they would be the winner.

There are many reasons to prefer Condorcet-certified electoral methods, but simply switching the electoral systems of the state contests wouldn’t achieve what Maskin and Sen want, that is, the President always having won a majority of the popular vote. There are a couple of reasons for this, and I hinted at one in my post on bellwethers: party candidates and Presidents alike are not chosen by the popular vote. Rather, in both primaries and general elections the voters in each state select delegates, and those delegates vote for the nominee or President. (There’s also a really wonkish criticism to be made of their choice of words: a Condorcet winner is not the same thing as a majority winner.

For example, Maskin and Sen mention1 that John Kerry might have won Florida in the 2004 Presidential Election if a Condorcet method had been in place. That’s because Kerry won 47.09% of the vote, and Bush won 52.10%, with Nader taking 0.43%. Had Nader been out of the contest, or a Condorcet voting method been in place, Kerry might have won Florida. That’s true, and it’s the same reason why Ted Cruz and John Kasich kinda-sorta made a deal to avoid splitting their vote against Trump. But winning the popular vote state-by-state is not at all the same thing as winning the national popular vote: Al Gore did win the nationwide popular vote in 2004, and he still didn’t win the Presidency. He could have won the Presidency if he had gained the same number of votes but distributed differently between the states. The same applies to the 1876 and 1888 elections.

In other words, even if the state-level contests meet the Condorcet criterion, that doesn’t mean that the national contest will when taken as a whole. It depends crucially on how many delegates each state gets (as well as on how the state’s delegates are allocated to candidates based on the result of the state’s popular vote: winner-takes-all, or proportionally, or some other method).

All in proportion

Currently, delegates to the general election’s Electoral College are not assigned to states proportionally to their population, but based on Congressional apportionment (party conference delegates are assigned in a similar, but not identical, way). A single Electoral College delegate can represents between 200 000 and 700 000 voters depending on the state.

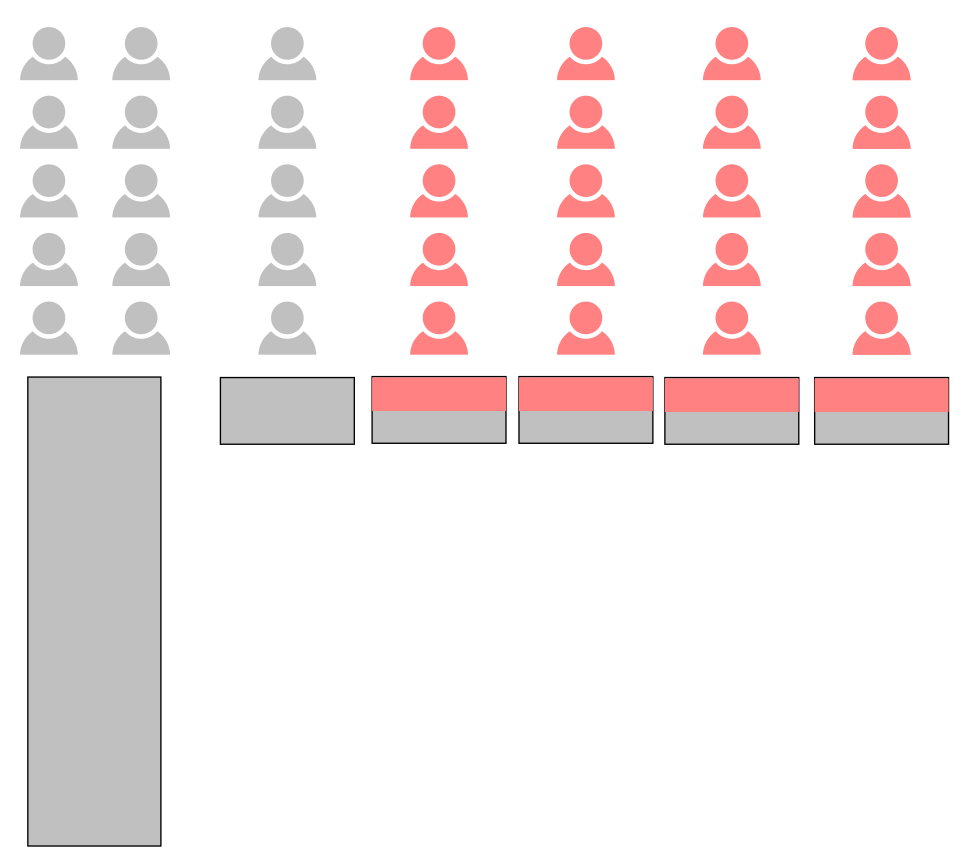

To see how this works, consider a country made up of one large state with 7 million voters and five small states with 1 million each. Let’s say the large state chooses 10 electors, and each of the small states chooses 5. This give the states voter-to-delegate ratios similar to the extremes of the current Electoral College. The large state is clearly underrepresented, having 7x more population but only 2x more votes. A candidate could win this election by narrowly winning 4 of the small states — 500 000 votes and 5 delegates in each, for a total of 20 out of 35 delegates. But they would only have won 2.5 million (20%) of the 12 million popular votes. Notice that this happens even though the winning candidate has a strict majority in each of the states they win, which is a more “fair” outcome than Maskin and Sen even hope for!

This example is simplified, but the outcome is no more extreme than is possible in the real US system. If a candidate won very slight absolute majorities in the 31 states most highly represented in the Electoral College, they could become President on 23.0% of the popular vote. Given 54.9% turnout, that’s just 12.6% of eligible voters. And that’s assuming two parties: with an arbitrarily large number of parties, a President could win with an arbitrarily small share of the vote!

The state-level voting system which Maskin and Sen want to improve is only half the story. Once a state is won, it’s just as important how much that result counts towards the national contest.

The Condorcet and Majority criteria

Maskin and Sen also slightly mangle two criteria for the fairness of voting systems: the Condorcet criterion and the Majority criterion.

The Condorcet criterion says that

if there is a candidate who would beat each of the others in one-on-one contests then that candidate should win

while the Majority criterion says that

if there is a candidate who wins an absolute majority of the votes then that candidate should win

Different voting systems can satisfy one or the other criterion, but a system which satisfies the Condorcet criterion automatically satisfies the Majority criterion. That’s easy to see: any a candidate who beats each of their opponents one-on-one will also beat all of them combined (because they can only do worse by splitting the vote).

But the opposite is not true: a system which satisfies the majority criterion does not necessarily satisfy the Condorcet criterion. Imagine a candidate who beat their opponents one-on-one, but did not command an absolute majority. They would be elected by a Condorcet system, but not necessarily by a majority system. The Condorcet criterion is in that sense more strict, more difficult to satisfy. Majority winners are few and far between, so it’s not that hard to guarantee that when they exist they are chosen.

The direction of implication is slightly tricky here, and Maskin and Sen get it a bit wrong. Both of the criteria say that if a candidate exists who meets these parameters, then they win. They do not say that a Condorcet or majority winner must exist; in a Condorcet or majority system, the winner does not have to be able to beat all of their opponents one-on-one or gain an absolute majority. Why is this? Think of the majority case: if votes are split 60/20/20, then the candidate with 60% wins, and the majority criterion holds. If the vote is split 40/30/30, there is no candidate with an absolute majority, so the majority criterion says nothing about who should win! Plurality voting — our familiar win-if-you-win-the most votes system that Maskin and Sen complain about — satisfies the majority criterion! In fact, you could have a voting system where if there was no absolute majority the winner was selected randomly from all the candidates in the field, and that would still meet the majority criterion!

Maskin and Sen also confuse matters by saying that a candidate who “would defeat each opponent individually in a head-to-head match-up” is “a real majority winner”. Well, if you take the common-sense meaning of “majority”, that’s not true. A Condorcet winner could be a majority winner, but they don’t have to be. If they’re redefining “majority” to mean someone who beats other candidates one-on-one head-to-head, they’re twisting the meaning of the word. Beating your opponents one-on-one is perhaps a desirable property, but it’s just not the same thing as having a majority. If you want plurality winners to stop behaving as if they had a majority, you should feel the same about mere Condorcet winners.

Majority rules

So should we just elect the President by nationwide popular vote? Not necessarily: the current electoral system might seem arbitrary or plain weird, and parts of it certainly are. But state-level contests are designed to cement the importance of the states in the electoral system. In fact, while the Constitution provides that the states choose the Electoral College, it doesn’t say that the popular vote has anything to do with it. That’s for the state legislatures to decide, and it wasn’t until 1872 that all states held popular elections for President. There is a debate to be had as to whether the power of the people or the power of the states is more important.

Regardless of the details of the American system, Maskin and Sen’s more general point is that plurality winners should be humble, and remember that a whole bunch of their constituents didn’t vote for them. True. But winners should be humble even if they have a majority: even after the most indisputable victory not every voter approves of every policy a politician come up with during their term in office. It’s a fundamental — one might say necessary — characteristic of representative democracy that elected representatives don’t perfectly mirror the opinions of the citizenry. Democracy’s in the details.

-

Correction 2016-05-22 Maskin and Sen’s original article actually used the example of George W. Bush, Al Gore and Ralph Nader in Florida in 2000. The substantive point stands, however. ↩